India's Biometric Identity System Tracks Nearly a Billion People

With nearly a billion people signed on, India has the largest biometric identity system in the world. The Aadhaar identity system requires citizens and residents to submit biometric data as proof of their identity. With too few protections in place, the system opens participants up to number of risks ranging from identity theft to all-pervasive mass surveillance, opponents warn.

With nearly a billion people signed on, India has the largest biometric identity system in the world. The Aadhaar identity system requires citizens and residents to submit biometric data as proof of their identity. With too few protections in place, the system opens participants up to number of risks ranging from identity theft to all-pervasive mass surveillance, opponents warn.

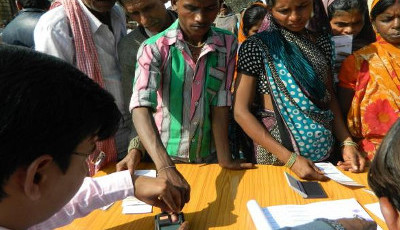

Aadhaar is a 12-digit unique identification (UID) number serving as a proof of identity for all residents of India. The number is tied to uniquely identifying biometric and demographic data. The biometric data consists of a photograph, 10 fingerprints and 2 iris scans. The demographic data required is a name, gender, address and date of birth.

Although the Aadhaar system has been in use for years, it did so on shaky legal grounds because it wasn't backed up by a legislative mandate. But last week the Lok Sabha, India's lower house of parliament passed the Aadhaar bill (Targeted Delivery of Financial and Other Subsidies, Benefits and Services), cementing Aadhaar's position further.

Access to services and subsidies

Many of India's residents do not have any official means to identify themselves. Lack of identification – which is especially prevalent among the rural poor - makes it difficult to access government services like food stamps, fossil fuel subsidies and pensions, and partake in transactions such as getting a loan or an insurance. On the other hand, the lack of a uniform identification system has rendered government services vulnerable to fraud, in the form of ghost beneficiaries being signed up to collect subsidies.

To tackle these problems the government of India started working on a national ID system for all residents by founding the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) in 2009. In 2010 the UIDAI launched the Aadhaar program.

One database to rule them all

The country of 1.2 billion residents has issued 980 million Aadhaar numbers so far. The Chief Architect of the Aadhaar technology, Dr. Pramod Varma, is proudly calling it the “world's largest biometric identity system”. But the object of his pride is someone else's Orwellian nightmare. All that uniquely identifying data of nearly a billion people is collected in a single central database, the Central Identities Data Repository (CIDR). A design choice that makes both privacy advocates and security experts shudder.

CIDR will become a magnet for cybercriminals and foreign state actors. “The chances of getting a central database compromised depend on the nature of information stored in it. For the sake of security one can't create a honey pot to be attacked by many. The internet is secure because it doesn't have a central database”, Sunil Abraham, Executive Director of Bangalore Centre for Internet and Society, told Business Standard in an interview. “Biometric information should be stored on smart cards and under no circumstances should there be a central repository of biometrics at one place. Maintaining a central database is akin to getting the keys of every house in Delhi and storing them at a central police station.”

Aadhaar is a 12-digit unique identification (UID) number serving as a proof of identity for all residents of India. The number is tied to uniquely identifying biometric and demographic data. The biometric data consists of a photograph, 10 fingerprints and 2 iris scans. The demographic data required is a name, gender, address and date of birth.

Although the Aadhaar system has been in use for years, it did so on shaky legal grounds because it wasn't backed up by a legislative mandate. But last week the Lok Sabha, India's lower house of parliament passed the Aadhaar bill (Targeted Delivery of Financial and Other Subsidies, Benefits and Services), cementing Aadhaar's position further.

Access to services and subsidies

Many of India's residents do not have any official means to identify themselves. Lack of identification – which is especially prevalent among the rural poor - makes it difficult to access government services like food stamps, fossil fuel subsidies and pensions, and partake in transactions such as getting a loan or an insurance. On the other hand, the lack of a uniform identification system has rendered government services vulnerable to fraud, in the form of ghost beneficiaries being signed up to collect subsidies.

To tackle these problems the government of India started working on a national ID system for all residents by founding the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) in 2009. In 2010 the UIDAI launched the Aadhaar program.

One database to rule them all

The country of 1.2 billion residents has issued 980 million Aadhaar numbers so far. The Chief Architect of the Aadhaar technology, Dr. Pramod Varma, is proudly calling it the “world's largest biometric identity system”. But the object of his pride is someone else's Orwellian nightmare. All that uniquely identifying data of nearly a billion people is collected in a single central database, the Central Identities Data Repository (CIDR). A design choice that makes both privacy advocates and security experts shudder.

CIDR will become a magnet for cybercriminals and foreign state actors. “The chances of getting a central database compromised depend on the nature of information stored in it. For the sake of security one can't create a honey pot to be attacked by many. The internet is secure because it doesn't have a central database”, Sunil Abraham, Executive Director of Bangalore Centre for Internet and Society, told Business Standard in an interview. “Biometric information should be stored on smart cards and under no circumstances should there be a central repository of biometrics at one place. Maintaining a central database is akin to getting the keys of every house in Delhi and storing them at a central police station.”