Worm compass identified

For years researchers have sought to identify the sensor which some creatures use in order to navigate. Animals as diverse as migrating geese, sea turtles and wolves are known to use the Earth's magnetic field. Until now, no one has pinpointed quite how they do it...

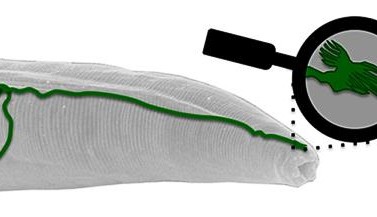

For years researchers have sought to identify the sensor which some creatures use in order to navigate. Animals as diverse as migrating geese, sea turtles and wolves are known to use the Earth's magnetic field. Until now, no one has pinpointed quite how they do it. The sensor, found in worms called C. elegans, is a microscopic structure at the end of a neuron that other animals probably share, given similarities in brain structure across species. The sensor looks like a nano-scale TV antenna, and the worms use it to navigate underground.

The researchers discovered that hungry worms in gelatin-filled tubes tend to move down, a strategy they might use when searching for food. When the researchers brought worms into the lab from other parts of the world, they didn't all move down. Depending on where they were from — Hawaii, England or Australia, for example — they moved at a precise angle to the magnetic field that would have corresponded to down if they had been back home. For instance, Australian worms moved upward in tubes. The magnetic field’s orientation varies from spot to spot on Earth, and each worm's magnetic field sensor system is finely tuned to its local environment, allowing it to tell up from down.

The researchers discovered the worms' magnetosensory abilities by altering the magnetic field around them with a special magnetic coil system and then observing changes in behavior. They also showed that worms which were genetically engineered to have a broken AFD neuron did not orient themselves up and down as do normal worms. Finally, the researchers used a technique called calcium imaging to demonstrate that changes in the magnetic field cause the AFD neuron to activate.

The research is published this week in the journal eLife. The study's lead author is Andrés Vidal-Gadea, a former postdoctoral researcher in the College of Natural Sciences at UT Austin, now a faculty member at Illinois State University. He noted that C. elegans is just one of myriad species living in the soil, many of which are known to migrate vertically.

Source: The University of Texas at Austin.

The researchers discovered that hungry worms in gelatin-filled tubes tend to move down, a strategy they might use when searching for food. When the researchers brought worms into the lab from other parts of the world, they didn't all move down. Depending on where they were from — Hawaii, England or Australia, for example — they moved at a precise angle to the magnetic field that would have corresponded to down if they had been back home. For instance, Australian worms moved upward in tubes. The magnetic field’s orientation varies from spot to spot on Earth, and each worm's magnetic field sensor system is finely tuned to its local environment, allowing it to tell up from down.

The researchers discovered the worms' magnetosensory abilities by altering the magnetic field around them with a special magnetic coil system and then observing changes in behavior. They also showed that worms which were genetically engineered to have a broken AFD neuron did not orient themselves up and down as do normal worms. Finally, the researchers used a technique called calcium imaging to demonstrate that changes in the magnetic field cause the AFD neuron to activate.

The research is published this week in the journal eLife. The study's lead author is Andrés Vidal-Gadea, a former postdoctoral researcher in the College of Natural Sciences at UT Austin, now a faculty member at Illinois State University. He noted that C. elegans is just one of myriad species living in the soil, many of which are known to migrate vertically.

Source: The University of Texas at Austin.