Controlling BLDC Motors: A Beginner’s Guide

on

Brushed DC motors are simple to use because the commutation method is mechanical. The position of the carbon brushes in relation to the commutator ensures that the appropriate coils are powered at precisely the right moment with respect to the magnetic field generated by the permanent magnets.

BLDC motors, on the other hand, require electronic commutation. The wiring for each coil is brought out of the casing, and the developer is responsible for powering them in the correct order.

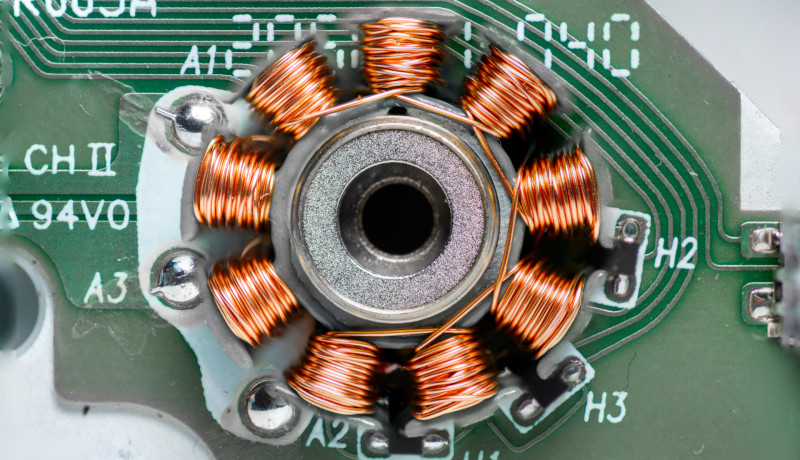

Motor Structure

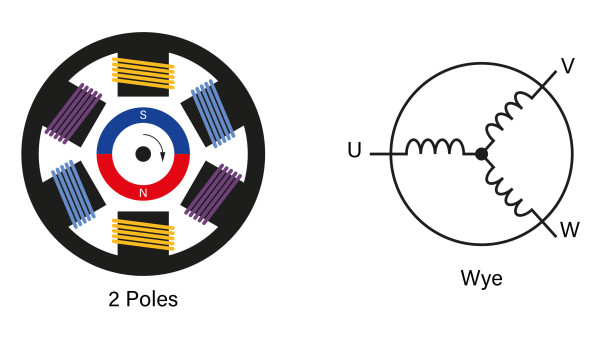

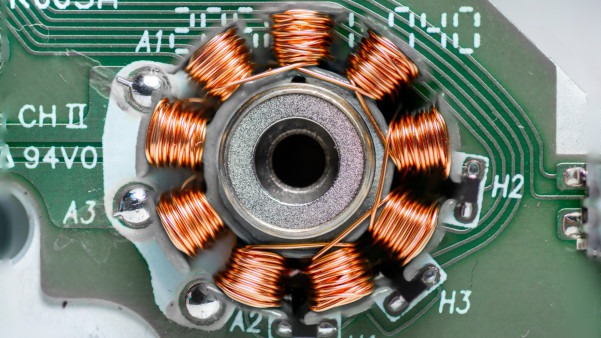

Before tackling the electrical control, its necessary to understand the mechanical construction of a brushless DC motor. A BLDC motor typically has three wires; in many articles on their use, they are named U, V, and W. The permanent magnet is found affixed to the rotor, while the coil windings (stator) are attached to the motor housing.

There are also many different variants of BLDC motors designed to meet the needs of specific applications. For example, for drones and model aircraft, outrunner motors are popular. Here the stator is in the middle, and the rotor and its permanent magnets are on the outside. Cooling can improve as a result, and the higher inertia of the design helps maintain a stable motor speed. Despite the differences, the control approach remains the same.

the stator coils in the center. Such motors are popular in drones and RC model aircraft.

Commutating the Motor

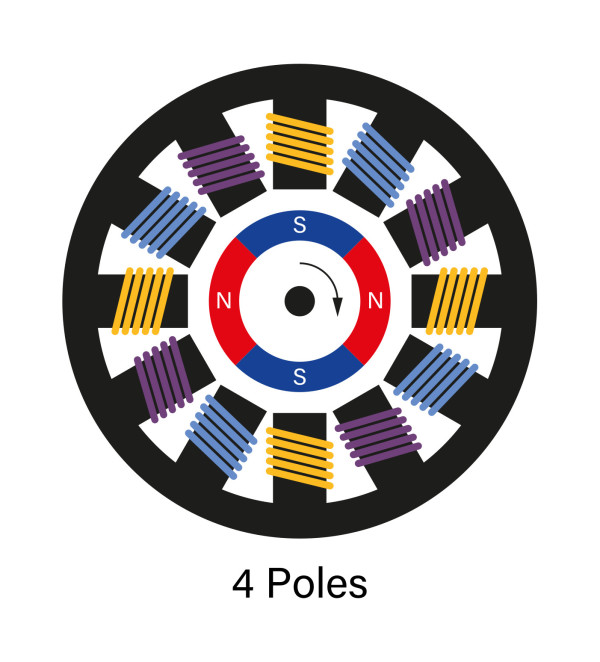

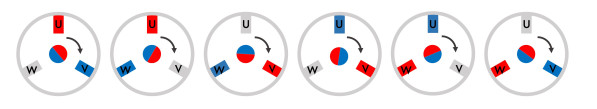

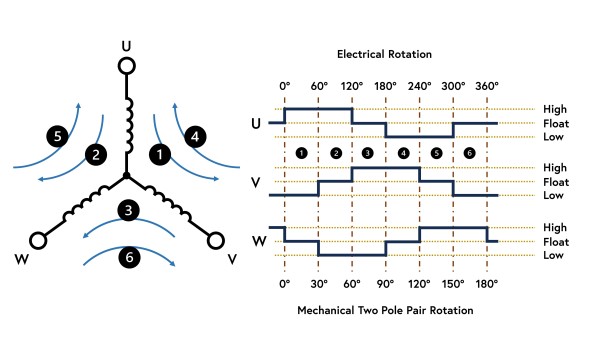

Because the rotor is the part with the permanent magnetic, it is the job of the design engineer to create a rotating magnetic field that the rotor follows. This means the stator coils must be energized in a specific order. Each stator needs to be energized once as a north pole and once as a south pole. With three stators, this means we have a sequence of six steps to implement electronic commutation.

Red is the north pole, blue is south.

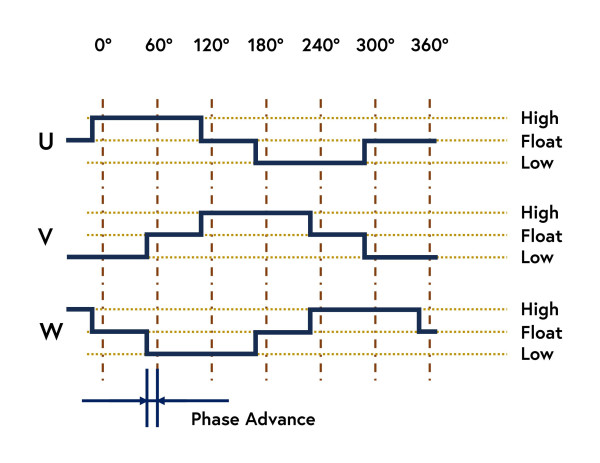

while the diagram shows when the phases are connected to high, low, or left floating.

The difference between electrical and mechanical rotation is also shown.

Because the coils have a very low resistance, leaving a coil powered for any length of time is also risky. This can occur when a debugger with a microcontroller is used and a breakpoint is reached. Some microcontrollers targeting BLDC motor control applications can disengage their control pins when the debugger halts the microcontroller.

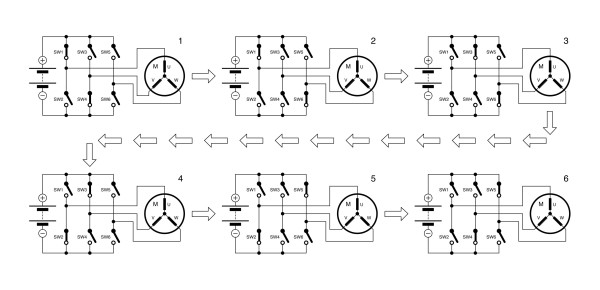

a three-phase bridge. The switches are typically implemented using MOSFETs or IGBTs.

Another important consideration is the load on the processor. At 100 RPM, you have 600 ms (60 seconds ÷ 100) to execute the code for a single rotation of a single pole pair motor. For a four-pole pair motor, you need to be able to execute the same code in just 150 ms (a quarter of the time). At 1,000 RPM, this drops to 60 ms and 15 ms, respectively.

When your code for maintaining speed is also considered (typically a PID controller), the load on the processor can be exceptionally high and even limit the RPM the motor can achieve. This is why many microcontroller vendors offer devices dedicated to motor control, with peripherals that offload much of the complexity into hardware.

Getting the Order Right and at the Correct Time – Rotor Position Sensors

So, which coil pair do you engage first? Well, it’s a one-in-six chance of guessing correctly. To resolve this, many motors either have a rotor sensor or have provision for attaching one. At the low-cost end are Hall sensors. These typically provide a resolution of 60° or better (360° ÷ 6 for a single pole pair motor). At the top end are resolvers, an analog sensor that can provide sub-degree rotor angle feedback. Your microcontroller or integrated BLDC driver chip will read this sensor before engaging the first coil pair so that the current rotor angle is known.

The advantage of knowing the rotor position before engaging the coils is that it stops a sudden jerking of the rotor to match the position of the applied magnetic field. Of course, knowledge of the rotor position is critical throughout motor commutation, ensuring that the next correct pair of coils are engaged as the rotor rotates. The sensor’s feedback is also passed to the control algorithm, enabling speed to be maintained even as the load changes.

Controlling BLDC Motor Speed

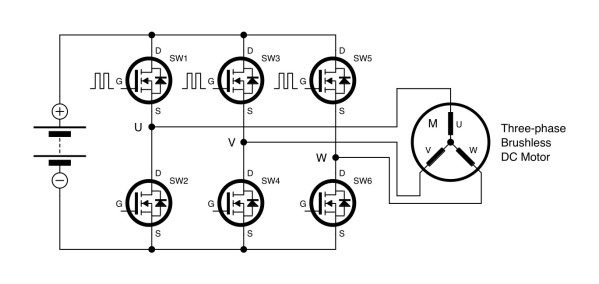

With the rotor position clear and the ability to power the correct pair of stator coils at the correct moment, the next step is controlling the motor’s speed. This is done in exactly the same manner as with a brushed DC motor: by varying the voltage.Referring back to the three-phase bridge circuit, the three upper MOSFETs are usually connected to microcontroller pins capable of producing a pulse-width modulated (PWM) output. At a low mark-space ratio, the voltage applied to the stator coils is low. As a result, the motor rotates slowly, and, using the feedback from the Hall sensor, the microcontroller changes the output signals to implement the six-step commutation process at the appropriate speed. As the voltage increases, so does the rotor speed and the rate at which the microcontroller works through the six commutation steps.

Note that applying a load to the rotor causes it to slow down unless a speed control algorithm (PID) has been implemented.

points enable control of the motor's speed.

More Advanced BLDC Control Approaches

Like everything in electronics, you can always refine control if you can find a way to manage the complexity! For example, a sensor on the rotor adds weight, makes the motor larger, costs money, and is an additional source of potential failure.Instead, the back-EMF of the motor can be monitored using an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) that monitors the motor phases that are not being driven or connected to ground. This requires analog and digital filtering due to the noise in such circuits, placing further load on the processor. One issue with this approach is that a static rotor produces no back-EMF, thus it is challenging to determine the rotor angle at rest. However, some clever approaches and software algorithms can overcome this.

If you want to drive the motor faster than specified, this is also possible. Simply configure the commutation software to change to the next commutation step a little earlier than required, i.e., pre-empt the next commutation step. Termed phase advance in documentation, motors can achieve more than double the datasheet maximum RPM. However, this comes at a torque loss and electrical efficiency drop.

can be pushed beyond its datasheet limit. The penalty for this is a loss of torque and efficiency.

Chips for BLDC Motor Control

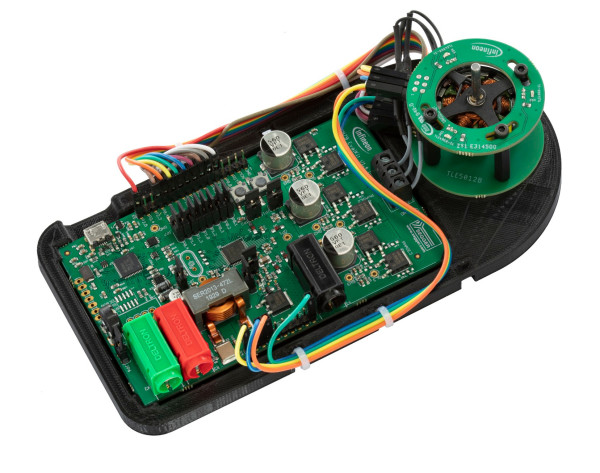

Searching for appropriate silicon to implement BLDC motor control can be confusing, as there are many providers for different sections of the system. Companies like Microchip and Infineon offer microcontrollers dedicated to motor control. These are often supported by current, angle, and position sensors. Others focus on the connection between the microcontroller and the three-phase bridge. The MOSFETs used often require a significant amount of power to drive their gates, so vendors such as Elmos, Toshiba, and Monolithic Power (MPS) offer (pre-)drivers. Such devices also provide short circuit protection, dead time control, and even small linear regulators to power the microcontroller and other circuitry.

sensors, for a rapid start into the world of BLDC motors. (Source: Infineon)

Discussion (28 comments)