Critical Engineering: Exposing Information Technology’s Hidden Agenda

April 03, 2013

on

on

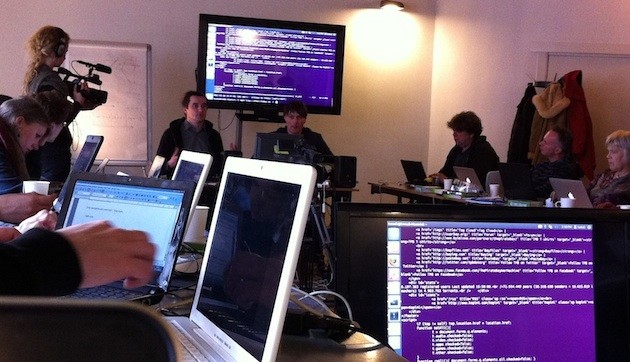

Who controls the Internet? To explore this question I participated in the five day NETworkshop Behind the Screens of the Internet. The question is too multilayered to yield a singular definitive answer but the crash course in computer networking made one thing painfully clear: it isn’t We The People.

Critical EngineersJulian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev taught the NETworkshop. In their view -as laid down in The Critical Engineering Manifesto- engineering is rapidly becoming the most dominant of languages, its expression shaping our reality. If people don’t understand that language, they’re unable to actively engage in deciding what reality should look like. That’s why Critical Engineers aim to make opaque engineering designs transparent and spread techno-political literacy.

The NETworkshop, designed both to reveal the political dimension of the internet and provide hands-on knowledge about how the internet works, was organized by Dorien Zandbergen, a cultural transition researcher at Leiden University, Waag Society and Netwerk Democratie [Dutch]. It took place in Amsterdam, March 25 – 29.

Politics of engineering

Engineering, Danja and Julian say, has a tremendous impact on society. When you build a bridge across a river, connecting two previously separate communities, everything changes. New trading routes change the economy, cultures intermingle and languages mutually influence each other. As it alters our circumstances engineering changes the way we think. The International Space Station has caused a shift in our understanding of ourselves. We no longer think of humanity as inseparable from its home planet but rather a species that could live anywhere in the universe, like an Iain M. Banks Culture novel.

But you don’t need to be able to build a bridge to understand what it does and how it influences your life. ‘Its function is expressed outwardly’, says Julian. ‘With contemporary technology that’s different. A smartphone, for instance, is very abstract. It is unclear how it works. When technology stops being self-describing or indescribable it’s a black box.’

Locking users out of the inner workings of technology is not merely a marketing decision, it’s a political decision, Julian points out. It keeps the user in the dark about what they’re actually dealing with, depriving them of the ability to make informed decisions. If pocket computers hadn’t been framed as cell phones but as tracking devices with a phone function, perhaps people would’ve used them differently.

The more dependent people are on a technology the more dangerous obfuscation is. If engineering is indeed the language with which reality is constructed than the practice of willfully hiding its intended meaning throws us into a futuristic equivalent of the Dark Ages, replacing Latin with code.

Techno-political literacy

To not only tell but also show us the political implications of technical implementations Danja and Julian taught us how to build our own computer network. And as we build a miniature mirror image of the internet over the course of days, it became crystal clear that a user conducting -let’s call it- ordinary internet behavior, gives everything away. Every step of the way.

The surrender of autonomy starts, for most people, at their own computer. The proprietary operating system stands between them and full access to their machine. So our first step was to install Linux to acquire superuser status.

The cables we used to connect our mini-internet were provided by our host The Waag Society, they’re a nice bunch so that wasn’t a problem. In the real world, however, the cables connecting the network of networks are owned by privately owned corporations. Julian related a story about him visiting people in Lima, Peru. Using a technique called packet tracing he showed his hosts that their international bound data was trafficked over a submarine cable owned by Spanish company Telefonica. For historical reasons, Peruvians aren’t to keen on the idea of a Spanish corporation having so much power over their communications.

Danja’s computer (Base) was designated as Domain Name System (DNS) server of our network. The DNS server translates web addresses that humans can remember into machine-readable IP-addresses. Despite the popular image of the internet as a decentralized network DNS makes it very hierarchical and centralized indeed. All our requests to connect to another computer had to go through Base and Danja could follow exactly who connected to who. And so can your Internet Service Provider (ISP) which provides the DNS server. If you are in the Netherlands, or any other country with a data retention law in place, ISPs are required to retain that data for six to twelve months. Just in case the government needs it.

Privately owned data centers, data gathering search engines, open unencrypted wireless networks, uniquely identifiable MAC addresses, data selling social networks, always-on beacons, packet headers, Terms of Service… After five days of NETworkshopping, my view on my position in the internet landscape has changed quite dramatically. I’m exposed. Insecure. My traffic logged. My data retained by God knows who, for who knows what.

Time to make some changes.

Danja, Julian and many others wrote the CryptoPartyHandbook. A good place to start.

Critical EngineersJulian Oliver and Danja Vasiliev taught the NETworkshop. In their view -as laid down in The Critical Engineering Manifesto- engineering is rapidly becoming the most dominant of languages, its expression shaping our reality. If people don’t understand that language, they’re unable to actively engage in deciding what reality should look like. That’s why Critical Engineers aim to make opaque engineering designs transparent and spread techno-political literacy.

The NETworkshop, designed both to reveal the political dimension of the internet and provide hands-on knowledge about how the internet works, was organized by Dorien Zandbergen, a cultural transition researcher at Leiden University, Waag Society and Netwerk Democratie [Dutch]. It took place in Amsterdam, March 25 – 29.

Politics of engineering

Engineering, Danja and Julian say, has a tremendous impact on society. When you build a bridge across a river, connecting two previously separate communities, everything changes. New trading routes change the economy, cultures intermingle and languages mutually influence each other. As it alters our circumstances engineering changes the way we think. The International Space Station has caused a shift in our understanding of ourselves. We no longer think of humanity as inseparable from its home planet but rather a species that could live anywhere in the universe, like an Iain M. Banks Culture novel.

But you don’t need to be able to build a bridge to understand what it does and how it influences your life. ‘Its function is expressed outwardly’, says Julian. ‘With contemporary technology that’s different. A smartphone, for instance, is very abstract. It is unclear how it works. When technology stops being self-describing or indescribable it’s a black box.’

Locking users out of the inner workings of technology is not merely a marketing decision, it’s a political decision, Julian points out. It keeps the user in the dark about what they’re actually dealing with, depriving them of the ability to make informed decisions. If pocket computers hadn’t been framed as cell phones but as tracking devices with a phone function, perhaps people would’ve used them differently.

The more dependent people are on a technology the more dangerous obfuscation is. If engineering is indeed the language with which reality is constructed than the practice of willfully hiding its intended meaning throws us into a futuristic equivalent of the Dark Ages, replacing Latin with code.

Techno-political literacy

To not only tell but also show us the political implications of technical implementations Danja and Julian taught us how to build our own computer network. And as we build a miniature mirror image of the internet over the course of days, it became crystal clear that a user conducting -let’s call it- ordinary internet behavior, gives everything away. Every step of the way.

The surrender of autonomy starts, for most people, at their own computer. The proprietary operating system stands between them and full access to their machine. So our first step was to install Linux to acquire superuser status.

The cables we used to connect our mini-internet were provided by our host The Waag Society, they’re a nice bunch so that wasn’t a problem. In the real world, however, the cables connecting the network of networks are owned by privately owned corporations. Julian related a story about him visiting people in Lima, Peru. Using a technique called packet tracing he showed his hosts that their international bound data was trafficked over a submarine cable owned by Spanish company Telefonica. For historical reasons, Peruvians aren’t to keen on the idea of a Spanish corporation having so much power over their communications.

Danja’s computer (Base) was designated as Domain Name System (DNS) server of our network. The DNS server translates web addresses that humans can remember into machine-readable IP-addresses. Despite the popular image of the internet as a decentralized network DNS makes it very hierarchical and centralized indeed. All our requests to connect to another computer had to go through Base and Danja could follow exactly who connected to who. And so can your Internet Service Provider (ISP) which provides the DNS server. If you are in the Netherlands, or any other country with a data retention law in place, ISPs are required to retain that data for six to twelve months. Just in case the government needs it.

Privately owned data centers, data gathering search engines, open unencrypted wireless networks, uniquely identifiable MAC addresses, data selling social networks, always-on beacons, packet headers, Terms of Service… After five days of NETworkshopping, my view on my position in the internet landscape has changed quite dramatically. I’m exposed. Insecure. My traffic logged. My data retained by God knows who, for who knows what.

Time to make some changes.

Danja, Julian and many others wrote the CryptoPartyHandbook. A good place to start.

Read full article

Hide full article

Discussion (0 comments)