The EU’s energy strategy: adapting too slowly

on

The EU’s energy strategy:

adapting too slowly

The European Commission has updated for the second time the energy strategy for the European Union, as it does every two years. Although the new strategy, “Energy 2020”, sounds a more urgent note than the two previous editions, it does not offer much in the way of new plans or insights. It also generated few reactions in energy circles in Brussels. The strategy, which was published on 10 November, will be discussed by EU leaders during a summit on energy on 4 February 2011. The idea is that it will then be agreed upon by EU leaders at another EU summit in March 2011 to become the framework for all new EU energy policy initiatives – at least until the next update, in late 2012.

|

| Energy Commissioner Günther Oettinger identifies five policy priorities |

‘The price of failure is too high’. Energy 2020 sounds an urgent note right from the start. ‘Energy is the life blood of our society’, says the document. ‘The energy challenge is one of the greatest tests our society has to face. It will take decades to steer our energy systems onto a more secure and sustainable path.’ The Commission notes that investments of €1 trillion (€1,000 billion) are needed in generation and infrastructure. Urgent decisions have to be made ‘that will be felt over the next 30 years and more’. This calls for ‘an ambitious policy framework. Postponing these decisions will have immeasurable repercussions on society as regards both longer-term costs and security.’

The Commission notes that at this moment ‘Europe’s energy systems are adapting too slowly’. The European Council adopted in 2007 ambitious energy and climate change objectives (the famous 20-20-20 goals), but ‘the existing strategy is currently unlikely to achieve all the 2020 targets, and it is wholly inadequate to the longer term challenges.’

The Energy 2020 Strategy first sets out what is wrong in the European energy market today, according to the Commission:

- The internal market is still fragmented and there are still many barriers to open and fair competition.

- The security of internal supplies is undermined by delays in investments and insufficient technological progress.

- Efforts by the member states to improve energy efficiency are inadequate.

- There is no common approach towards external suppliers of oil and gas.

The root problem, says the Commission, is that energy is still too much a concern of the member states, whereas ‘the EU is the level at which energy policy should be developed’.

The Commission, under the leadership of the new Energy Commissioner Günther Oettinger, addresses the problems by identifying five policy priorities. Four of those five have already been on the agenda for quite some time: energy efficiency, the single energy market, technological progress and external relations. They are accompanied by one completely new priority: the protection and satisfaction of consumers.

Priority no. 1: Energy efficiency

The Commission notes that the ‘the quality of National Energy Efficiency Action Plans, developed by member states since 2008, is disappointing, leaving vast potential untapped’. This is despite the fact that energy efficiency is recognised as the most economic way of meeting the EU’s energy and climate change goals. The Commission estimates potential energy savings to be in the order of €1,000 per year per citizen.

Not for the first time the Commission urges EU member states to show an example by incorporating energy efficiency criteria into public procurement activities. Public procurement accounts for 16% of the EU’s gross domestic product (GDP), i.e. €1,500 billion, and could have a huge effect on creating a market for energy-efficient product and services. Local authorities are – at last – cited as major players

| ‘For years we have failed to direct substantial EU funds into energy policy. This is something which must end’ - Jerzy Busek, President of the European Parliament |

The Commission will come out with its own Energy Efficiency action plan in 2011. This updated version of its 2006 action plan has already been postponed several times. It will include regulatory proposals for financing mechanisms and incentives for investment in energy efficiency, in particular by using EU structural funds. The Energy 2020 Strategy does not contain any legislative proposals in this area and merely sets out a list of good intentions.

Priority no.2: The single energy market

|

| EU member states are still not talking with a single voice on energy and climate change issues |

The Commission explains that ‘the market is still largely fragmented into national markets with numerous barriers to open and fair competition’, because of different rules and national practices. Member states are riding roughshod over the application of EU law, with over 40 infringement proceedings relating to the second liberalisation package of 2003 alone. The Commission threatens – once again – that it will apply legislation, but without really baring its teeth. This despite the fact that data in the annexes show that some markets are oligopolies and even quasi-monopolies, such as in Belgium and Greece.

‘The previous Commission undertook at least some action to prevent cartels and market dominance. The Energy 2020 strategy has no concrete reference to new actions in the field of anti-competitive behaviour’, points out Claude Turmes, a “Green” Member of the European Parliament and long-time energy specialist. ‘Oettinger's cabinet is refusing to make any reference to a second market inquiry, although this demand has been supported by a large majority in the European Parliament’s Industry Committee.’

Priority no.3: Citizens

At last, the Commission seems to realise that liberalisation does not make any sense without consumers being involved and satisfied. The cause of consumers has gained momentum in the last years with the creation of a dedicated Forum of discussion. ‘A well-functioning, integrated internal

| ‘We urge Commissioner Oettinger to be bold in the legislative proposals that should follow’ - Christian Kjaer, Chief Executive Officer of the European Wind Energy Association (EWEA) |

‘Proposing initiatives is not enough: we need binding measures that regulators must be able to enforce’, comments Johannes Klein, spokesman of the European consumers’ organisation (BEUC). ‘This strategy is a lot about innovation and technology, such as smart metering. But what is missing here are the benefits for the consumers.’

The Commission also uses this short chapter as an opportunity to talk about safety: off-shore drilling, nuclear safety and the safety of new energy technologies (hydrogen and CO2 storage and transport for example).

Priority no.4: Technological progress

The Commission states that the EU’s leadership in the area of renewable energy sources (RES) is beginning to crumble in the face of competition from the US and China. It says that ‘priority should be given to renewable energies’ to guarantee that two-thirds of electricity will be low carbon by 2020 by comparison with 44% now (including nuclear and hydro). The Commission wants the strategy to provide a framework to ‘ensure that the renewable energy sources and technologies are economically competitive by 2020’.

‘We see that the European market is emphasized, but we are very afraid, that the issue is not sufficiently and properly addressed’, warns Susanne Nies, Head of Unit Energy Policy and Generation at

| ‘We see that the European market is emphasized, but we are very afraid that the issue is not sufficiently and properly addressed’ - Susanne Nies, Head of Unit Energy Policy and Generation at Eurelectric |

The Commission focuses on achieving the Strategic Energy Technology (SET) plan, aiming at boosting research in innovating low-carbon technologies: second generation biofuels, intelligent networks, carbon capture and storage, storage of electricity and transport running on electricity, fourth generation nuclear energy and heating/air conditioning based on renewable energies.

About nuclear energy, the strategy says that it should be ‘assessed openly and objectively’ and that, ‘given the renewed interest in this form of generation in Europe and worldwide, research must be pursued on radioactive waste management technologies and their safe implementation, as well as preparing the longer term future through development of next generation fission systems and … and nuclear fusion (ITER)’.

Foratom, the trade association representing the interests of the European nuclear industry, is satisfied with this reference to nuclear power. ‘This strategy document confirms the political support that exists at EU level for nuclear energy’ and ‘gives a ringing endorsement of the key role that nuclear energy plays in helping the EU meet its energy security, competitiveness and low-carbon objectives’, Foratom notes rather grandly.

Of course financing these technology development is essential, but for this the strategy so far has no practical solution. ‘For years we have failed to direct substantial EU funds into energy policy. This is something which must end’, reacts Jerzy Busek, President of the European Parliament. ‘In order to achieve progress and to be credible’, Busek promises he will fight for getting five billion euros for the SET-plan in the next budget of the EU for the period 2014-2020, on which negotiations have just started.

Priority no.5: External policy

|

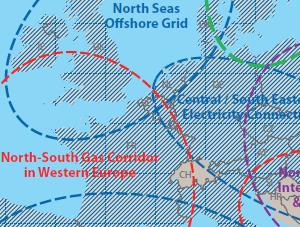

| Map of the EU infrastructure package. Click to see full map |

Hence, the Commission once again complains that EU member states are still not talking with a single voice to the outside world on energy and climate change issues. Will it be easier now that there is a chapter on energy in the EU’s Lisbon Treaty? That remains to be seen, given the new institutional organisation of the EU, which enhances competition between the EU’s high representatives (the President of the European Council Hermann van Rompuy, the President of the European Commission José Manuel Barroso and the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs Catherine Ashton), adding to the cacophony of different messages coming from the capitals of EU member states. Ideally, it would be best to coordinate the EU’s external energy policy with other external policies (development, trade, climate change and biodiversity, enlargement, foreign affairs etc.) and their respective instruments, but that ideal seems far out of reach.

Political courage

The new energy strategy has generated only a lukewarm response in Brussels. Many stakeholders did not even take the trouble to react. The general feeling is that although the Commission does identify the

| ‘The previous Commission undertook at least some action to prevent cartels and market dominance. The Energy 2020 strategy has no concrete reference to new actions in the field of anti-competitive behaviour’ - Claude Turmes |

One area in which the Commission does seem to be moving forward is that of infrastructure. A week after the Energy 2020 strategy was published, the Commission came out with an “infrastructure communication” that is a lot more concrete and is generating much more response than the strategy. We will have more to say about this next week.

Despite the lack of concrete progress, the EU leaders are likely to agree to the strategy, just as they have done before. In the past, EU leaders have always tended to improvise in their reactions to supply crises or price hikes. They avoid working on the substance, for instance on legislation for emergency stocks, security of supply policy or reducing their oil dependence, and tend to rely on ad hoc policy. They will not be frightened by an EU energy strategy that does not, at the end of the day, challenge the status quo.

Could it even be possible that the strategy is vague on purpose? ‘We urge Commissioner Oettinger to be bold in the legislative proposals that should follow’, says Christian Kjaer, Chief Executive Officer of the European Wind Energy Association (EWEA). ‘The test will be the strength of these proposals and the willingness to national governments to support them.’

Let’s imagine that, with such a vague work plan, Oettinger really manages to put Europe on the road towards genuinely having a sustainable energy policy and secure energy supply. He would have pulled off quite a coup and would deserve full credit for his efforts.

Discussion (0 comments)