From MENA and South-East Asia to Latin America: the regional expansion of the Energy Charter

October 07, 2015

on

on

2035 Energy Investment Needs – the cornerstone of Global Energy Security and Climate Challenge.

The latest steep fall in oil prices opened a new chapter for the development of global energy markets. Although it is not the first time we witness the oil price cycle, the one we are seeing today is of a different nature compared to its predecessors. If the oil price rise in 1970s was driven by demand and the fall of 2008 by supply, the fall of 2014 is clearly both supply- and demand-driven.

While the consequences of the necessary rebalancing of global energy markets remain to be seen, the status quo disguises a number of long-term challenges. One of the latter is about ensuring the necessary investments in the Middle East for meeting the future oil demand. In that respect, the complex geopolitical dynamics in the region cast serious concerns over oil supply and demand balances in the coming decades.

Cheap oil has been very welcomed by the energy-consuming countries; while it has been facilitating economic growth and creating the momentum to reduce fossil fuel subsidies in a number of countries (e.g. Indonesia).

At the same time, the availability of energy sources required to meet future demand cannot be taken for granted. According to the IEA, some $2 trillion of investments are needed annually to keep up with energy needs by 2035, out of which $40 trillion should be invested in energy supply and $8 trillion in energy efficiency correspondingly. What is more, about half of this $40 trillion investment bill accounts for energy supply projects (i.e. upstream oil and gas to compensate for declining production volumes of the existing ones; replacement of ageing electricity infrastructure). [1]

The above mentioned figure for the investments required in energy efficiency would be nearly twice as high, however, if we consider the scenario of trying to stay at or below 2°C of warming: $14 trillion by 2023. Although the energy efficiency policies of such countries as China are starting to bear fruit, global CO2 emissions are still on the rise and the carbon footprint of the major emitters is only increasing. [2]

Against the backdrop of climate challenges and the global security of supply, energy markets have been moving towards heavily regulated models, as the role of governmental policies on the national and regional level has become the key determinant of the investment climate. [3]

Hence, the need for addressing the issues of energy governance, energy security and sustainability on the transnational and governmental level is becoming more and more acute.

To this end, such initiatives as the one of the International Energy Charter are reinforced by the momentum, given the declaration’s broad geographical scope and ambitious proposals for international energy cooperation.

Indeed, the line of evolution and expansion of the Energy Charter over the last five years has been converging with global energy trends. Although the energy efficiency and infrastructure investments are quite substantial in the OECD countries, some 2/3 of the investments globally are to take place in the emerging economies in Asia, the MENA region, Africa and Latin America. [4] Countries from these regions have been actively involved in the Energy Charter’s modernisation process, and a number of them have adopted the Energy Charter Treaty to boost investments in their energy sector.

Conceived as a European project to boost energy cooperation between Europe and countries of the Former Soviet Union in the 1990s, the Energy Charter started its modernization process back in 2010 (for further information see Article II: The Road from the European to the International Energy Charter).

As a result of this Process, the International Energy Charter was negotiated and adopted this year in The Hague (20-21 May) by 75 countries and 3 international organisations (the European Union, the European Atomic Energy Community and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)) from 5 continents across the globe (for further information see Article II).

Today, we can draw some conclusions regarding the successful policy tools employed by the Energy Charter Conference member countries and the Secretariat, as well as attempt to trace the global and regional dynamics which contributed to creating the momentum for the new-coming countries to adopt the International Energy Charter.

The modus operandi of the Energy Charter’s CONEXO policy is underpinned by three elements:

a) intergovernmental cooperation, i.e. the Energy Charter Liaisons Embassies (ECLEs);

b) addressing common energy challenges through regional and global organisations (e.g. the Energy Charter’s cooperation with ECOWAS, which signed the International Energy Charter in The Hague and is now an observer organisation to the Energy Charter Conference);

c) capacity building and knowledge sharing through secondments to the Energy Charter’s Secretariat in Brussels; events, such as the Industry Advisory Panel meetings (for further information see The Energy Charter: Good Practices for Facilitating a Predictable Investment Climate in the Energy Industry); and other fora and initiatives.

On the intergovernmental level, the establishment of the Energy Charter Liaisons Embassies (ECLEs) by the governments of ECT Contracting Parties evolved into a robust and efficient instrument for the Energy Charter’s political support in targeted countries. The table below gives an overview of the existing ECLEs (four more are being currently under discussion):

Moving to regional cooperation, a number of relevant organisations have Observer Status to the Energy Charter Conference: ECOWAS, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Baltic Sea Region Energy Cooperation (BASREC), the Organisation of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC), the CIS Electric Power Council, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE).

Apart from that, relevant MoUs were signed with the League of Arab States in 2012, while back in 2007 a Letter of Understanding on Cooperative Activities with the Secretariat was signed with the International Energy Forum. Another MoU is currently being discussed with the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM).

On the global level, the following International Organisations have Observer Status to the Energy Charter Conference: the International Energy Agency, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD); The World Bank, and the World Trade Organization.

This way, the Energy Charter is working with some key players on the global energy scene, as the scope of its activities is positioned in a horizontal manner vis-à-vis that of the above-mentioned organizations.

Finally, the adoption of the International Energy Charter in The Hague on 20-21 May 2015 proved itself particularly relevant for the prospective Energy Charter members (see International Energy Charter: The Emergence of The New Global Energy Governance Architecture).

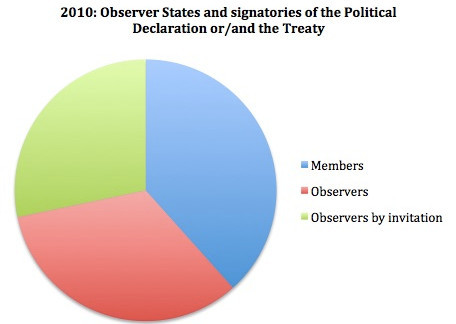

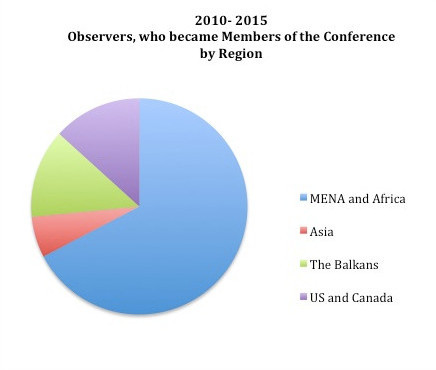

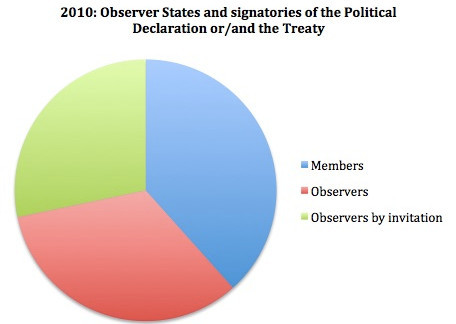

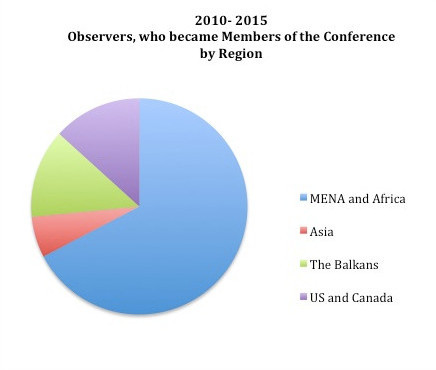

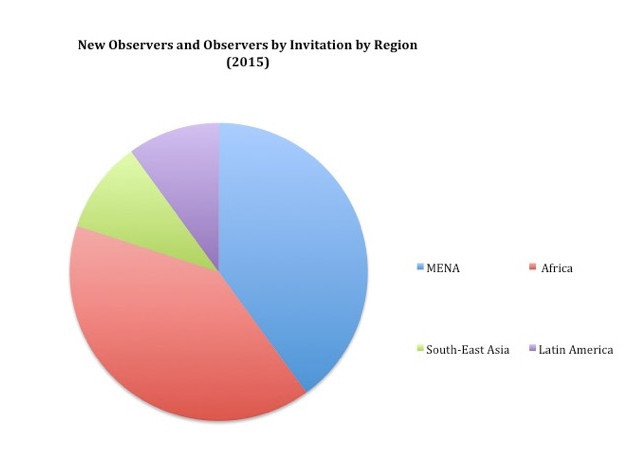

The transformations that the International Energy Charter brought about impacted both newcomers and the previous Energy Charters constituency. Looking at the time period between 2010 to 2015 (the evolution of the modernisation process) one can observe a clear shift within the Energy Charter’s constituency towards the adoption of the political declaration and accession to the Treaty by the former observers or observers by invitation.

The outcomes of the CONEXO policy between 2010 and 2015.

The highest number of countries who recently joined the Energy Charter process is by far from the MENA region.

Back in 2010, out of 24 Observer countries (read: Total number), 16 were from the MENA region (including Afghanistan and Pakistan). Within the last five years there has been a real breakthrough in terms of countries’ involvement in the Energy Charter and today the status quo is as follows:

If in 2010 some 20 countries had the status of Observers by Invitation from the region, now there are only 9: Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and the United Arab Emirates. The rest of the countries that used to be Observers from the region are either in the process of signing the political declaration or already ratifying the Treaty.

Notably, Iran has been very active during the negotiations on the International Energy Charter, which is another example demonstrating the relevance of this document for global energy security.

The explicit MENA interest in the Energy Charter goes hand in hand with the regional and global energy dynamics mentioned previously. Adopting the standards of international law, investment protection and improving regulatory predictability is undoubtedly crucial for the countries in the region to secure investments across the energy value chain.

Apart from the benefits in terms of attracting investments in the fossil fuel exploration and production, the Energy Charter offers the use of the Energy Charter’s Protocol on Energy Efficiency, which in turn could be a source of guidance to develop relevant policies and regulations to boost energy efficiency on both national and regional levels.

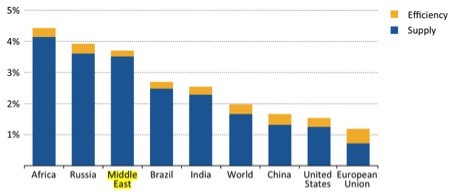

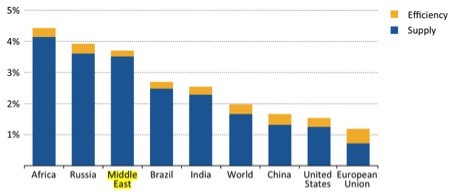

The IEA chart below gives an overview of cumulative energy investment needed (in energy supply and energy efficiency) per region as a share of GDP (2014-2035).

Chart 3: Cumulative energy investment as a share of GDP in the New Policies Scenario, 2014-2035

Source: IEA, WEIO, 2014

Investments in energy production in the Middle East are indeed pivotal, for both regional and global markets, as the current oil price cycle alone brings substantial challenges for securing the future oil supply volumes from the region. According to the IEA, the shortfall of investments in Middle East oil production could lead to the oil price peaking at $130/barrel in 2025. [5]

To this end, the Energy Charter provides the necessary tools to increase markets’ transparency, strengthen regulatory stability and thus provide greater security for the existing and prospective investors in the region.

Looking back at Chart 3, one can clearly see the investment challenge ahead of Africa. At the same time, energy security and alleviation of energy poverty are not less important for the countries on the continent. According to the IEA, only 290 million out of 915 million people have access to electricity in sub-Saharan Africa, and the total number without access to energy is only increasing.

Alleviation of energy poverty and ensuring universal energy access is indeed one of the key goals of the International Energy Charter, along with providing security of energy supply, demand and transit.

Many African countries have been actively promoting Energy Charter initiatives and the Charter’s cooperation with ECOWAS on the regional level, which only strengthens the Energy Charter’s presence in the region. Chad and Niger signed both the 1991 and the 2015 political declarations, while Nigeria, Mauritania, Morocco, Tanzania and Mozambique are currently preparing ECT accession reports.

The adoption of the International Energy Charter and taking steps towards the accession to the Energy Charter Treaty is definitely a clear message to the international community and stakeholders about the willingness of governments to keep their national policies in line with international standards.

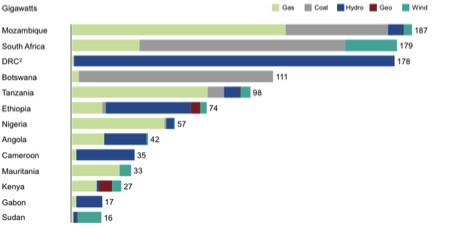

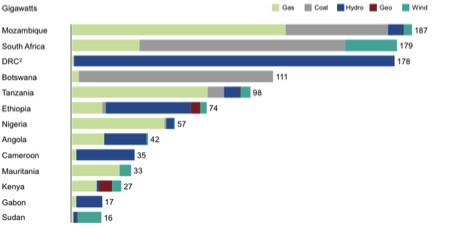

Establishing a stable regulatory and legal climate is undoubtedly key to fighting energy poverty and realizing the energy potential of such regions as sub-Saharan Africa. According to the recent McKinzey report “Brighter Africa”, only seven countries—Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Ghana, Namibia, Senegal and South Africa—have electricity access rates exceeding 50 percent. At the same time, there is extraordinary energy potential in the region (see Chart 4), which can only be unlocked with the help of foreign investors.

Chart 4: Power-generation potential for select sub-Saharan African countries by technology

Source: “Brighter Africa”, Report, McKinzey 2015

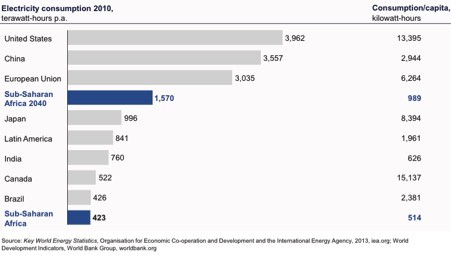

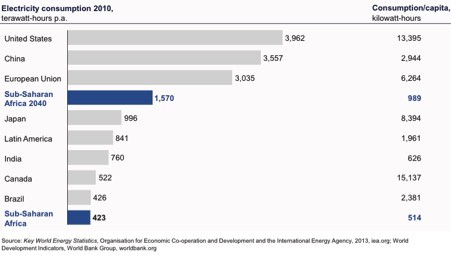

If one follows the demand-driven approach drawn in the report, the projected consumption of sub-Saharan Africa could be nearly 1,600 terawatt hours by 2040. In other words, by 2040, sub-Saharan Africa will consume as much electricity as India and Latin America combined did in 2010 (Chart 4).

Chart 5: Power consumption in sub-Saharan African 2040 vs 2010

Source: “Brighter Africa”, Report, McKinzey 2015

Sub-Saharan Africa has definitely become a new frontier of the Energy Charter’s expansion.

One of the initiatives relevant for the region has been a capacity building programme (financed by European Commission’s Directorate-General (DG) for International Development and Cooperation (DEVCO)) based on the secondments of officials from selected African countries to the Secretariat in Brussels in order to facilitate their understanding and accession to the International Energy Charter and the ECT.

More than 10 African countries joined the Energy Charter Process in 2015. The DEVCO Project enabled several countries from sub-Saharan Africa to prepare pre-assessment reports as a first step into their engagement in the Energy Charter Process. The missions to Kigali, Rwanda, and Maputo, Mozambique, were supported by the EU Delegations, and the Embassies of the Netherlands and Turkey have facilitated the participation of many African countries in the Energy Charter Process in a short timeframe.

Among the African countries which took part in the Ministerial Conference in The Hague, Benin, Burundi, Chad, Tanzania, and Uganda signed the International Energy Charter, while Botswana and Burkina Faso have adopted it. This brings the number of sub-Saharan African countries involved in the Energy Charter Process to 10. This is a very notable development, which has occurred in a very short period of time.

The active involvement of the African countries in the Energy Charter Process demonstrates that the latter is perceived as a solid institutional basis to strengthen the investment policy in the region.

Moving to North-East Asia, the signing of the International Energy Charter by China is by far one of the most important developments in terms of Charter’s expansion regionally and globally (for more information on Energy Charter and China see article China and the Emerging Global Energy Governance Architecture). [6]

Against the background of economic and energy transition in China, the expansion of outward and inward foreign investments in China’s energy sector clearly underlines the relevance of the International Energy Charter and the ECT as instruments for building confidence and regulatory stability in energy markets, as well as for securing energy transit in the region, and for the provision of mechanisms for addressing and settlement of disputes.

Most recently, an Industry Advisory Panel (IAP) meeting took place in Beijing (21 July 2015). [7] At the meeting, the role of the Energy Charter Treaty was analysed in terms of its relevance for promoting energy investments and contributing to China’s “One Belt One Road” initiative, as well as in securing energy transit at a regional scale. This meeting highlighted the potential benefits of the ECT in terms of China’s outward investment protection, enhancing confidence in China’s domestic legal environment and increasing China’s influence and involvement in global energy governance structures.

The Secretariat has started re-engaging with a number of countries in Asia. Back in 2004, the ECT was formally discussed at the ASEAN Senior Officers’ Meeting on Energy, and relations with Asian countries have been recently re-activated in the view of the negotiations over the new political declaration. As a result, Cambodia and The Philippines adopted the International Energy Charter.

Working with ASEAN (which is strengthening further economic and institutional integration), the Energy Charter is gaining new momentum in the region, and countries such as Vietnam are planning to sign the IEC in the coming months.

The Secretariat, together with other international partners, also works closely to facilitate the Regional Renewable Energy Cooperation in Northeast Asia. Finally, together with the Korean Energy Economics Institute (a government institution), the Secretariat is preparing a publication on the potential of the ECT in Asia, which is an example of the strong interest in the Energy Charter on Korea’s part.

US engagement in the Energy Charter and signing of the International Energy Charter declaration is a very positive and strong signal of country’s support of the Charter, as well as willingness to take part in this emerging global energy governance structure. At the ministerial conference in The Hague, US officials highlighted the role of the Energy Charter in alleviating energy poverty globally and its importance in creating a stable, secure and transparent investment climate in developing countries. This topic, along with global energy security, is definitely one of the pivots of US involvement in the Charter’s activities. It would be interesting to see how the transatlantic energy dialogue will be evolving in the framework of the Energy Charter, against the background of the ongoing TTIP negotiations.

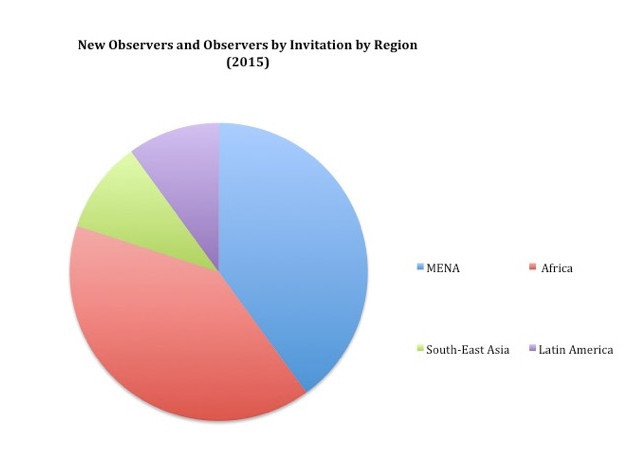

Such countries as Chile and Colombia also signed the International Energy Charter, thereby becoming Observers to the Energy Charter Conference. Overall, when it comes to Latin America, there are a number of challenges that countries in the region are currently facing, but also some significant opportunities that can be unlocked if the necessary investments in the energy sector are secured.

Firstly, Latin America is not immune to the issue of energy access, as it affects some 20% of the population in the region. Another critical issue is that of interconnections between the markets – e.g. Chile, Peru and Colombia – which partly has to do with the lack of a single framework on the regional level that would facilitate it. To this end, the Energy Charter has the potential to provide single rules and a level-playing field for the countries in the region, underpinned by a secure and stable environment for investors. This way, non-commercial risks can be substantially reduced and institutional stability would pave the way for the flow of capital in the energy industries across the region.

Apart from Chile and Colombia, which by signing the International Energy Charter became Observers to the Energy Charter Conference, the countries that are showing their interest in the Energy Charter include Costa Rica, El Salvador and Guatemala. Another group of countries comprised of Uruguay, Bolivia and Paraguay have voiced their willingness to continue and improve their learning process on the Energy Charter, with the support of the Secretariat.

Considering the ambitious energy efficiency goals in the region, the improvement of regional investment protection is indeed one of the top priorities to succeed on the regional level.

Good practices in improving regional cooperation, the certainty that it brings to investors without any technological bias, as well as the stable market rules it can provide – these are some key benefits that the countries in the region that adopted the International Energy Charter identify. While their political support of the Charter has been clear, the accession to the Treaty is currently being considered by Chile and Colombia.

To conclude, having looked into the Energy Charter’s expansion dynamics on the regional level, one can observe that the drivers behind the movement towards the Charter vary depending on a country’s profile. However, be it an energy consuming country, energy producer or transit state, the issues of holistic energy security, underpinned by the need for a favourable and stable environment for investments, are universal. The Energy Charter’s relevance for countries that need to attract large capital investments in their energy industry and/or secure their outward investments and energy transit is clear. To this end, the scope of the Energy Charter’s policies and legal provisions covers a wide range of issues across the entire energy value chain, which creates advantages in its positioning vis-à-vis other international organisations addressing energy issues.

At the same time, the ambition of the Energy Charter’s constituency to create a global energy governance structure is strengthened by its commitment to alleviating energy poverty and moving towards sustainable and secure energy markets.

The adoption of the International Energy Charter gave a new impetus both within and outside the Energy Charter’s constituency: a number of observers and observers by invitation became ECT Contracting Parties, while new member countries have come on board by signing the political declaration in The Hague. One may well argue that this process coincides with regional and global energy market dynamics, which in turn reinforce the relevance of the Energy Charter in meeting the 2030 global investment challenge, as well as boosting the sustainability of energy systems.

The successful wider uptake of the Energy Charter Treaty will now depend on the modernisation process that it is currently undergoing (the so-called Phase II). Hence, for countries that intend to influence the Energy Charter’s evolution and enforce the principles of energy cooperation that it promotes, this is an important moment for engagement.

1. IEA World Energy Investment Outlook 2014

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. IEA World Energy Investment Outlook 2014

6. Also, see the relevant Energy Charter Publications, e.g. The report "Securing Energy Flows from Central Asia to China and the Relevance of the Energy Charter Treaty to China" available at www.energycharter.org.

7. For more information and presentations available online see www.energycharter.org

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the experts whom we have consulted in the course of writing this article for providing their valuable insights, in particular, Nidal Tayeh and Ernesto Bonafé from the Energy Charter Secretariat in Brussels and Juan Felipe Neira from the University of Dundee.

The Energy Charter Secretariat monitors the implementation of the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty and provides support to the Treaty-based international organisation, the Energy Charter Conference (52 states). The Treaty strengthens the rule of law on energy issues, by creating a level playing field of rules to be observed by all participating governments, thereby mitigating risks associated with energy-related investment and trade. The Treaty focuses on: the protection of foreign investments; non-discriminatory conditions for energy trade; reliable energy transit; the resolution of state-to-state and, in the case of investments, investor-state disputes; and energy efficiency policies.

The International Energy Charter is a political declaration adopted in The Hague on 20 May 2015. It is designed to spread fundamental principles of international energy cooperation to new partner countries.

This series of materials is part of a wider awareness-raising campaign aimed at promoting the renewed role and creating further momentum behind the Energy Charter in today’s global energy markets.

Image: Earthlights. Source: NASA. Public domain.

The latest steep fall in oil prices opened a new chapter for the development of global energy markets. Although it is not the first time we witness the oil price cycle, the one we are seeing today is of a different nature compared to its predecessors. If the oil price rise in 1970s was driven by demand and the fall of 2008 by supply, the fall of 2014 is clearly both supply- and demand-driven.

While the consequences of the necessary rebalancing of global energy markets remain to be seen, the status quo disguises a number of long-term challenges. One of the latter is about ensuring the necessary investments in the Middle East for meeting the future oil demand. In that respect, the complex geopolitical dynamics in the region cast serious concerns over oil supply and demand balances in the coming decades.

Cheap oil has been very welcomed by the energy-consuming countries; while it has been facilitating economic growth and creating the momentum to reduce fossil fuel subsidies in a number of countries (e.g. Indonesia).

At the same time, the availability of energy sources required to meet future demand cannot be taken for granted. According to the IEA, some $2 trillion of investments are needed annually to keep up with energy needs by 2035, out of which $40 trillion should be invested in energy supply and $8 trillion in energy efficiency correspondingly. What is more, about half of this $40 trillion investment bill accounts for energy supply projects (i.e. upstream oil and gas to compensate for declining production volumes of the existing ones; replacement of ageing electricity infrastructure). [1]

The above mentioned figure for the investments required in energy efficiency would be nearly twice as high, however, if we consider the scenario of trying to stay at or below 2°C of warming: $14 trillion by 2023. Although the energy efficiency policies of such countries as China are starting to bear fruit, global CO2 emissions are still on the rise and the carbon footprint of the major emitters is only increasing. [2]

Converging Pathways: Global Energy Trends and Evolution of the Energy Charter.

Against the backdrop of climate challenges and the global security of supply, energy markets have been moving towards heavily regulated models, as the role of governmental policies on the national and regional level has become the key determinant of the investment climate. [3]

Hence, the need for addressing the issues of energy governance, energy security and sustainability on the transnational and governmental level is becoming more and more acute.

To this end, such initiatives as the one of the International Energy Charter are reinforced by the momentum, given the declaration’s broad geographical scope and ambitious proposals for international energy cooperation.

Indeed, the line of evolution and expansion of the Energy Charter over the last five years has been converging with global energy trends. Although the energy efficiency and infrastructure investments are quite substantial in the OECD countries, some 2/3 of the investments globally are to take place in the emerging economies in Asia, the MENA region, Africa and Latin America. [4] Countries from these regions have been actively involved in the Energy Charter’s modernisation process, and a number of them have adopted the Energy Charter Treaty to boost investments in their energy sector.

The Energy Charter’s Modernisation Benchmarks

Conceived as a European project to boost energy cooperation between Europe and countries of the Former Soviet Union in the 1990s, the Energy Charter started its modernization process back in 2010 (for further information see Article II: The Road from the European to the International Energy Charter).

As a result of this Process, the International Energy Charter was negotiated and adopted this year in The Hague (20-21 May) by 75 countries and 3 international organisations (the European Union, the European Atomic Energy Community and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)) from 5 continents across the globe (for further information see Article II).

Today, we can draw some conclusions regarding the successful policy tools employed by the Energy Charter Conference member countries and the Secretariat, as well as attempt to trace the global and regional dynamics which contributed to creating the momentum for the new-coming countries to adopt the International Energy Charter.

CONEXO Policy Instruments: Intergovernmental, Regional and Global

The modus operandi of the Energy Charter’s CONEXO policy is underpinned by three elements:

a) intergovernmental cooperation, i.e. the Energy Charter Liaisons Embassies (ECLEs);

b) addressing common energy challenges through regional and global organisations (e.g. the Energy Charter’s cooperation with ECOWAS, which signed the International Energy Charter in The Hague and is now an observer organisation to the Energy Charter Conference);

c) capacity building and knowledge sharing through secondments to the Energy Charter’s Secretariat in Brussels; events, such as the Industry Advisory Panel meetings (for further information see The Energy Charter: Good Practices for Facilitating a Predictable Investment Climate in the Energy Industry); and other fora and initiatives.

On the intergovernmental level, the establishment of the Energy Charter Liaisons Embassies (ECLEs) by the governments of ECT Contracting Parties evolved into a robust and efficient instrument for the Energy Charter’s political support in targeted countries. The table below gives an overview of the existing ECLEs (four more are being currently under discussion):

Moving to regional cooperation, a number of relevant organisations have Observer Status to the Energy Charter Conference: ECOWAS, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Baltic Sea Region Energy Cooperation (BASREC), the Organisation of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC), the CIS Electric Power Council, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE).

Apart from that, relevant MoUs were signed with the League of Arab States in 2012, while back in 2007 a Letter of Understanding on Cooperative Activities with the Secretariat was signed with the International Energy Forum. Another MoU is currently being discussed with the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM).

On the global level, the following International Organisations have Observer Status to the Energy Charter Conference: the International Energy Agency, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD); The World Bank, and the World Trade Organization.

This way, the Energy Charter is working with some key players on the global energy scene, as the scope of its activities is positioned in a horizontal manner vis-à-vis that of the above-mentioned organizations.

Finally, the adoption of the International Energy Charter in The Hague on 20-21 May 2015 proved itself particularly relevant for the prospective Energy Charter members (see International Energy Charter: The Emergence of The New Global Energy Governance Architecture).

The transformations that the International Energy Charter brought about impacted both newcomers and the previous Energy Charters constituency. Looking at the time period between 2010 to 2015 (the evolution of the modernisation process) one can observe a clear shift within the Energy Charter’s constituency towards the adoption of the political declaration and accession to the Treaty by the former observers or observers by invitation.

The outcomes of the CONEXO policy between 2010 and 2015.

MENA Region

The highest number of countries who recently joined the Energy Charter process is by far from the MENA region.

Back in 2010, out of 24 Observer countries (read: Total number), 16 were from the MENA region (including Afghanistan and Pakistan). Within the last five years there has been a real breakthrough in terms of countries’ involvement in the Energy Charter and today the status quo is as follows:

- Israel, Lebanon and Iran are currently exploring the next steps towards greater involvement in the Charter and potentially signing the IEC;

- ECT accession is pending in Pakistan and Jordan, while the Secretariat is currently providing support to Morocco and Mauritania, which have confirmed their intention to accede to the ECT in the near future; such countries as Yemen are currently in the accession process;

- Oman, Bahrein, Iraq and Qatar have also been showing their interest in the Energy Charter process.

If in 2010 some 20 countries had the status of Observers by Invitation from the region, now there are only 9: Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and the United Arab Emirates. The rest of the countries that used to be Observers from the region are either in the process of signing the political declaration or already ratifying the Treaty.

Notably, Iran has been very active during the negotiations on the International Energy Charter, which is another example demonstrating the relevance of this document for global energy security.

The explicit MENA interest in the Energy Charter goes hand in hand with the regional and global energy dynamics mentioned previously. Adopting the standards of international law, investment protection and improving regulatory predictability is undoubtedly crucial for the countries in the region to secure investments across the energy value chain.

Apart from the benefits in terms of attracting investments in the fossil fuel exploration and production, the Energy Charter offers the use of the Energy Charter’s Protocol on Energy Efficiency, which in turn could be a source of guidance to develop relevant policies and regulations to boost energy efficiency on both national and regional levels.

The IEA chart below gives an overview of cumulative energy investment needed (in energy supply and energy efficiency) per region as a share of GDP (2014-2035).

Chart 3: Cumulative energy investment as a share of GDP in the New Policies Scenario, 2014-2035

Source: IEA, WEIO, 2014

Investments in energy production in the Middle East are indeed pivotal, for both regional and global markets, as the current oil price cycle alone brings substantial challenges for securing the future oil supply volumes from the region. According to the IEA, the shortfall of investments in Middle East oil production could lead to the oil price peaking at $130/barrel in 2025. [5]

To this end, the Energy Charter provides the necessary tools to increase markets’ transparency, strengthen regulatory stability and thus provide greater security for the existing and prospective investors in the region.

Africa

Looking back at Chart 3, one can clearly see the investment challenge ahead of Africa. At the same time, energy security and alleviation of energy poverty are not less important for the countries on the continent. According to the IEA, only 290 million out of 915 million people have access to electricity in sub-Saharan Africa, and the total number without access to energy is only increasing.

Alleviation of energy poverty and ensuring universal energy access is indeed one of the key goals of the International Energy Charter, along with providing security of energy supply, demand and transit.

Many African countries have been actively promoting Energy Charter initiatives and the Charter’s cooperation with ECOWAS on the regional level, which only strengthens the Energy Charter’s presence in the region. Chad and Niger signed both the 1991 and the 2015 political declarations, while Nigeria, Mauritania, Morocco, Tanzania and Mozambique are currently preparing ECT accession reports.

The adoption of the International Energy Charter and taking steps towards the accession to the Energy Charter Treaty is definitely a clear message to the international community and stakeholders about the willingness of governments to keep their national policies in line with international standards.

Establishing a stable regulatory and legal climate is undoubtedly key to fighting energy poverty and realizing the energy potential of such regions as sub-Saharan Africa. According to the recent McKinzey report “Brighter Africa”, only seven countries—Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Ghana, Namibia, Senegal and South Africa—have electricity access rates exceeding 50 percent. At the same time, there is extraordinary energy potential in the region (see Chart 4), which can only be unlocked with the help of foreign investors.

Chart 4: Power-generation potential for select sub-Saharan African countries by technology

Source: “Brighter Africa”, Report, McKinzey 2015

If one follows the demand-driven approach drawn in the report, the projected consumption of sub-Saharan Africa could be nearly 1,600 terawatt hours by 2040. In other words, by 2040, sub-Saharan Africa will consume as much electricity as India and Latin America combined did in 2010 (Chart 4).

Chart 5: Power consumption in sub-Saharan African 2040 vs 2010

Source: “Brighter Africa”, Report, McKinzey 2015

Sub-Saharan Africa has definitely become a new frontier of the Energy Charter’s expansion.

One of the initiatives relevant for the region has been a capacity building programme (financed by European Commission’s Directorate-General (DG) for International Development and Cooperation (DEVCO)) based on the secondments of officials from selected African countries to the Secretariat in Brussels in order to facilitate their understanding and accession to the International Energy Charter and the ECT.

More than 10 African countries joined the Energy Charter Process in 2015. The DEVCO Project enabled several countries from sub-Saharan Africa to prepare pre-assessment reports as a first step into their engagement in the Energy Charter Process. The missions to Kigali, Rwanda, and Maputo, Mozambique, were supported by the EU Delegations, and the Embassies of the Netherlands and Turkey have facilitated the participation of many African countries in the Energy Charter Process in a short timeframe.

Among the African countries which took part in the Ministerial Conference in The Hague, Benin, Burundi, Chad, Tanzania, and Uganda signed the International Energy Charter, while Botswana and Burkina Faso have adopted it. This brings the number of sub-Saharan African countries involved in the Energy Charter Process to 10. This is a very notable development, which has occurred in a very short period of time.

The active involvement of the African countries in the Energy Charter Process demonstrates that the latter is perceived as a solid institutional basis to strengthen the investment policy in the region.

North-East Asia

Moving to North-East Asia, the signing of the International Energy Charter by China is by far one of the most important developments in terms of Charter’s expansion regionally and globally (for more information on Energy Charter and China see article China and the Emerging Global Energy Governance Architecture). [6]

Against the background of economic and energy transition in China, the expansion of outward and inward foreign investments in China’s energy sector clearly underlines the relevance of the International Energy Charter and the ECT as instruments for building confidence and regulatory stability in energy markets, as well as for securing energy transit in the region, and for the provision of mechanisms for addressing and settlement of disputes.

Most recently, an Industry Advisory Panel (IAP) meeting took place in Beijing (21 July 2015). [7] At the meeting, the role of the Energy Charter Treaty was analysed in terms of its relevance for promoting energy investments and contributing to China’s “One Belt One Road” initiative, as well as in securing energy transit at a regional scale. This meeting highlighted the potential benefits of the ECT in terms of China’s outward investment protection, enhancing confidence in China’s domestic legal environment and increasing China’s influence and involvement in global energy governance structures.

The Secretariat has started re-engaging with a number of countries in Asia. Back in 2004, the ECT was formally discussed at the ASEAN Senior Officers’ Meeting on Energy, and relations with Asian countries have been recently re-activated in the view of the negotiations over the new political declaration. As a result, Cambodia and The Philippines adopted the International Energy Charter.

Working with ASEAN (which is strengthening further economic and institutional integration), the Energy Charter is gaining new momentum in the region, and countries such as Vietnam are planning to sign the IEC in the coming months.

The Secretariat, together with other international partners, also works closely to facilitate the Regional Renewable Energy Cooperation in Northeast Asia. Finally, together with the Korean Energy Economics Institute (a government institution), the Secretariat is preparing a publication on the potential of the ECT in Asia, which is an example of the strong interest in the Energy Charter on Korea’s part.

US and Latin America

US engagement in the Energy Charter and signing of the International Energy Charter declaration is a very positive and strong signal of country’s support of the Charter, as well as willingness to take part in this emerging global energy governance structure. At the ministerial conference in The Hague, US officials highlighted the role of the Energy Charter in alleviating energy poverty globally and its importance in creating a stable, secure and transparent investment climate in developing countries. This topic, along with global energy security, is definitely one of the pivots of US involvement in the Charter’s activities. It would be interesting to see how the transatlantic energy dialogue will be evolving in the framework of the Energy Charter, against the background of the ongoing TTIP negotiations.

Such countries as Chile and Colombia also signed the International Energy Charter, thereby becoming Observers to the Energy Charter Conference. Overall, when it comes to Latin America, there are a number of challenges that countries in the region are currently facing, but also some significant opportunities that can be unlocked if the necessary investments in the energy sector are secured.

Firstly, Latin America is not immune to the issue of energy access, as it affects some 20% of the population in the region. Another critical issue is that of interconnections between the markets – e.g. Chile, Peru and Colombia – which partly has to do with the lack of a single framework on the regional level that would facilitate it. To this end, the Energy Charter has the potential to provide single rules and a level-playing field for the countries in the region, underpinned by a secure and stable environment for investors. This way, non-commercial risks can be substantially reduced and institutional stability would pave the way for the flow of capital in the energy industries across the region.

Apart from Chile and Colombia, which by signing the International Energy Charter became Observers to the Energy Charter Conference, the countries that are showing their interest in the Energy Charter include Costa Rica, El Salvador and Guatemala. Another group of countries comprised of Uruguay, Bolivia and Paraguay have voiced their willingness to continue and improve their learning process on the Energy Charter, with the support of the Secretariat.

Considering the ambitious energy efficiency goals in the region, the improvement of regional investment protection is indeed one of the top priorities to succeed on the regional level.

Good practices in improving regional cooperation, the certainty that it brings to investors without any technological bias, as well as the stable market rules it can provide – these are some key benefits that the countries in the region that adopted the International Energy Charter identify. While their political support of the Charter has been clear, the accession to the Treaty is currently being considered by Chile and Colombia.

IEC: the emerging global energy governance framework.

To conclude, having looked into the Energy Charter’s expansion dynamics on the regional level, one can observe that the drivers behind the movement towards the Charter vary depending on a country’s profile. However, be it an energy consuming country, energy producer or transit state, the issues of holistic energy security, underpinned by the need for a favourable and stable environment for investments, are universal. The Energy Charter’s relevance for countries that need to attract large capital investments in their energy industry and/or secure their outward investments and energy transit is clear. To this end, the scope of the Energy Charter’s policies and legal provisions covers a wide range of issues across the entire energy value chain, which creates advantages in its positioning vis-à-vis other international organisations addressing energy issues.

At the same time, the ambition of the Energy Charter’s constituency to create a global energy governance structure is strengthened by its commitment to alleviating energy poverty and moving towards sustainable and secure energy markets.

The adoption of the International Energy Charter gave a new impetus both within and outside the Energy Charter’s constituency: a number of observers and observers by invitation became ECT Contracting Parties, while new member countries have come on board by signing the political declaration in The Hague. One may well argue that this process coincides with regional and global energy market dynamics, which in turn reinforce the relevance of the Energy Charter in meeting the 2030 global investment challenge, as well as boosting the sustainability of energy systems.

The successful wider uptake of the Energy Charter Treaty will now depend on the modernisation process that it is currently undergoing (the so-called Phase II). Hence, for countries that intend to influence the Energy Charter’s evolution and enforce the principles of energy cooperation that it promotes, this is an important moment for engagement.

1. IEA World Energy Investment Outlook 2014

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. IEA World Energy Investment Outlook 2014

6. Also, see the relevant Energy Charter Publications, e.g. The report "Securing Energy Flows from Central Asia to China and the Relevance of the Energy Charter Treaty to China" available at www.energycharter.org.

7. For more information and presentations available online see www.energycharter.org

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the experts whom we have consulted in the course of writing this article for providing their valuable insights, in particular, Nidal Tayeh and Ernesto Bonafé from the Energy Charter Secretariat in Brussels and Juan Felipe Neira from the University of Dundee.

The Energy Charter Secretariat monitors the implementation of the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty and provides support to the Treaty-based international organisation, the Energy Charter Conference (52 states). The Treaty strengthens the rule of law on energy issues, by creating a level playing field of rules to be observed by all participating governments, thereby mitigating risks associated with energy-related investment and trade. The Treaty focuses on: the protection of foreign investments; non-discriminatory conditions for energy trade; reliable energy transit; the resolution of state-to-state and, in the case of investments, investor-state disputes; and energy efficiency policies.

The International Energy Charter is a political declaration adopted in The Hague on 20 May 2015. It is designed to spread fundamental principles of international energy cooperation to new partner countries.

This series of materials is part of a wider awareness-raising campaign aimed at promoting the renewed role and creating further momentum behind the Energy Charter in today’s global energy markets.

Image: Earthlights. Source: NASA. Public domain.

Read full article

Hide full article

Discussion (0 comments)