Who Will Be Left Standing at the End of the Oil War

February 24, 2016

This is a financial cold war—nothing more, nothing less.

While there are billions of reasons to cut output, and every major producing country is reeling from the loss of revenues, some are weathering the current bust better than others, but the devil is in the details, and the details contain tons of variables.

Production cost and break-even figures that analysts enjoy bandying can trap you in bubble of black-and-white mathematics that is a few brush-strokes shy of a full picture.

Break-even prices are hard to pin down, and harder yet because they fluctuate. OPEC governments downsize their budgets, cut social spending and put big projects on hold to lower the break-even price. Independent producers likewise cut spending and delay development to get closer to a feasible break-even. So the break-even is elusive.

Saudi Arabia and Kuwait enjoy some of the lowest production costs in the world, at about $10 and $8.50, respectively, according to Rystad Energy data. Production in the UAE costs just over $12 per barrel, which is pretty much the same as in Iran, though Iranian officials say they will eventually be able to produce for as low as $1 per barrel from their central fields.

But these are just the costs of lifting oil out of the ground. State-owned oil companies often have many more responsibilities than just producing oil. They underpin generous spending levels by their governments, and thus any estimate of a "break-even" price should include the cost of those obligations.

It's hard to come up with a real break-even point for Saudi oil, for example, because it is responsible for funding the royal palace and indirectly, a large number of social programs that include everything from education to housing and energy subsidies. It's hard to measure costs when this oil has to pay for all the luxuries of the Saudi royal family.

According to Quartz, if you add in all these costs that U.S. shale producers don't have, we're looking at a break-even point of around $86 per barrel for Saudi oil. That's just one opinion, but it's a poignant one. So is the royal family ready to give up its luxuries? Or will they sacrifice things such as healthcare and education first? The fact that the government is considering taking parts of Saudi Aramco public does not bode well.

The Iranian perspective, newly off sanctions, is entirely different. It's probably more concerned about regaining the market share it lost under sanctions than it is about low prices. In June, Iran will launch a new grade of heavy crude that will compete with Basra crude, and which the Iranians will surely seek to undercut in price in order to win Asian market share from Iraq and the Saudis.

For Nigeria, Libya and Iraq, the break-even point is the point at which they can fund the fight against Boko Haram, a civil war and the Islamic State, respectively. Right now, they can't. And that's with per barrel production costs of around $31/$32 in Nigeria, $23/$24 in Libya, and $10/$11 in Iraq.

Then we have Venezuela, where production costs hover just over $23 per barrel on average, but where disaster is imminent. Debt defaults here are looming, and inflation is soaring, while recent moves to drastically devalue the currency and raise gas prices by over 6,000 percent for the first time in decades are harbingers of highly destabilizing unrest. For Venezuela, the break-even point is particularly elusive because the country's oil is very heavy and very dirty—and thus very expensive to extract and refine.

From the Saudi perspective, the end game here is to break the back of U.S. shale.

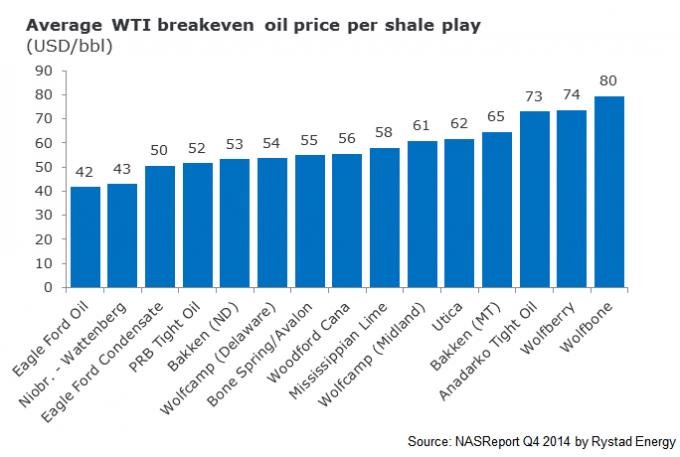

The average production costs for the U.S. is about $36 per barrel, but Rystad Energy estimates that some the key U.S. shale plays have a $58-per-barrel break-even point. This, too, varies section by section, and even well by well, so it's hard to get a concrete picture.

Here is the break-even picture in more detail, courtesy of Rystad Energy:

Plenty of shale areas are still profitable even with oil below $30, according to Bloomberg Intelligence—just ask Texas, where the Eagle Ford shale play's Dewitt County patch, for instance, can turn a profit even with crude below $23. Other counties, though, might need $58 to be profitable.

It's all about hedging right now for U.S. shale producers. The larger percentage of oil output that's protected by hedging, the longer the lifeline.

Last week, Denbury Resources Inc. (NYSE: DNR), for instance, said it had increased its fourth-quarter hedges to cover 30 Mbbl/d at around $38/bbl.

So far, "there is little evidence of production shut-ins for economic reasons," according to Wood Mackenzie's vice president of investment research, Robert Plummer. "Given the cost of restarting production, many producers will continue to take the loss in the hope of a rebound in prices."

The break-even is quite simply the line in the sand that determines whether extracting a barrel of oil is profitable or not. And this line in the sand is vastly different for private American producers than it is for kingdoms such as Saudi Arabia.

Everyone is hurting, some more than others. Venezuela is already on its knees. But even $30 oil isn't enough to bring the other bigger players down or to end the cold oil war. Saudi Arabia has some $600 billion in financial reserves; Russia is worried enough only to start talking to OPEC; U.S. producers are holding strong and are fairly calm, closely measuring the pace of desperation most recently indicated in the word game over an output freeze.

The variables of the break-even game favor U.S. shale. But Saudi Arabia won't give up the cold war path easily because its ultimate goal is to preserve its market share at all costs.

By Charles Kennedy for Oilprice.com. This article was originally published by Oilprice.com and is reproduced here with kind permission.

Image: Oil rigs. By: Anthony_goto. CC-BY licence.

While there are billions of reasons to cut output, and every major producing country is reeling from the loss of revenues, some are weathering the current bust better than others, but the devil is in the details, and the details contain tons of variables.

Production cost and break-even figures that analysts enjoy bandying can trap you in bubble of black-and-white mathematics that is a few brush-strokes shy of a full picture.

Break-even prices are hard to pin down, and harder yet because they fluctuate. OPEC governments downsize their budgets, cut social spending and put big projects on hold to lower the break-even price. Independent producers likewise cut spending and delay development to get closer to a feasible break-even. So the break-even is elusive.

Saudi Arabia and Kuwait enjoy some of the lowest production costs in the world, at about $10 and $8.50, respectively, according to Rystad Energy data. Production in the UAE costs just over $12 per barrel, which is pretty much the same as in Iran, though Iranian officials say they will eventually be able to produce for as low as $1 per barrel from their central fields.

But these are just the costs of lifting oil out of the ground. State-owned oil companies often have many more responsibilities than just producing oil. They underpin generous spending levels by their governments, and thus any estimate of a "break-even" price should include the cost of those obligations.

It's hard to come up with a real break-even point for Saudi oil, for example, because it is responsible for funding the royal palace and indirectly, a large number of social programs that include everything from education to housing and energy subsidies. It's hard to measure costs when this oil has to pay for all the luxuries of the Saudi royal family.

According to Quartz, if you add in all these costs that U.S. shale producers don't have, we're looking at a break-even point of around $86 per barrel for Saudi oil. That's just one opinion, but it's a poignant one. So is the royal family ready to give up its luxuries? Or will they sacrifice things such as healthcare and education first? The fact that the government is considering taking parts of Saudi Aramco public does not bode well.

The Iranian perspective, newly off sanctions, is entirely different. It's probably more concerned about regaining the market share it lost under sanctions than it is about low prices. In June, Iran will launch a new grade of heavy crude that will compete with Basra crude, and which the Iranians will surely seek to undercut in price in order to win Asian market share from Iraq and the Saudis.

For Nigeria, Libya and Iraq, the break-even point is the point at which they can fund the fight against Boko Haram, a civil war and the Islamic State, respectively. Right now, they can't. And that's with per barrel production costs of around $31/$32 in Nigeria, $23/$24 in Libya, and $10/$11 in Iraq.

Then we have Venezuela, where production costs hover just over $23 per barrel on average, but where disaster is imminent. Debt defaults here are looming, and inflation is soaring, while recent moves to drastically devalue the currency and raise gas prices by over 6,000 percent for the first time in decades are harbingers of highly destabilizing unrest. For Venezuela, the break-even point is particularly elusive because the country's oil is very heavy and very dirty—and thus very expensive to extract and refine.

Breaking the back of U.S. shale?

From the Saudi perspective, the end game here is to break the back of U.S. shale.

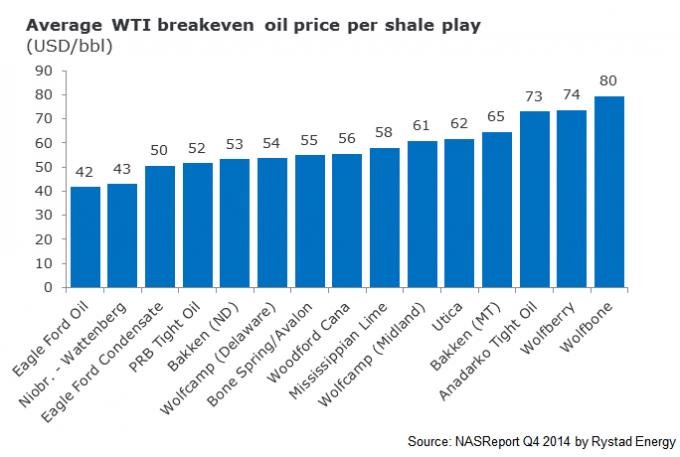

The average production costs for the U.S. is about $36 per barrel, but Rystad Energy estimates that some the key U.S. shale plays have a $58-per-barrel break-even point. This, too, varies section by section, and even well by well, so it's hard to get a concrete picture.

Here is the break-even picture in more detail, courtesy of Rystad Energy:

Plenty of shale areas are still profitable even with oil below $30, according to Bloomberg Intelligence—just ask Texas, where the Eagle Ford shale play's Dewitt County patch, for instance, can turn a profit even with crude below $23. Other counties, though, might need $58 to be profitable.

It's all about hedging right now for U.S. shale producers. The larger percentage of oil output that's protected by hedging, the longer the lifeline.

Last week, Denbury Resources Inc. (NYSE: DNR), for instance, said it had increased its fourth-quarter hedges to cover 30 Mbbl/d at around $38/bbl.

So far, "there is little evidence of production shut-ins for economic reasons," according to Wood Mackenzie's vice president of investment research, Robert Plummer. "Given the cost of restarting production, many producers will continue to take the loss in the hope of a rebound in prices."

The break-even is quite simply the line in the sand that determines whether extracting a barrel of oil is profitable or not. And this line in the sand is vastly different for private American producers than it is for kingdoms such as Saudi Arabia.

Everyone is hurting, some more than others. Venezuela is already on its knees. But even $30 oil isn't enough to bring the other bigger players down or to end the cold oil war. Saudi Arabia has some $600 billion in financial reserves; Russia is worried enough only to start talking to OPEC; U.S. producers are holding strong and are fairly calm, closely measuring the pace of desperation most recently indicated in the word game over an output freeze.

The variables of the break-even game favor U.S. shale. But Saudi Arabia won't give up the cold war path easily because its ultimate goal is to preserve its market share at all costs.

By Charles Kennedy for Oilprice.com. This article was originally published by Oilprice.com and is reproduced here with kind permission.

Image: Oil rigs. By: Anthony_goto. CC-BY licence.

Read full article

Hide full article

Discussion (1 comment)